“We had a bigger Jewish community when I was younger. We were very settled in Zambia with our own unique Jewish culture—a very welcoming and warm one,” she tells Chabad.org.

The first Jews arrived in Zambia (then called Northern Rhodesia) in the late 1800s, both chasing economic opportunity in cattle production and copper mining, and fleeing European antisemitism. Later, another wave of Jews came while seeking refuge from World War II and the Holocaust. In stark contrast to many in Europe, the local Zambian population welcomed the Jewish community with open arms.

“We have always had excellent support here,” says Shlomo Abutbul. “We can walk around in a kippah safely. This nation and its people are great supporters of Israel and the Jewish people.”

Shlomo grew up in a large, religious family in Herzliya, Israel. He and Bonnie met in Israel, where their oldest son, David, was born. Thirty years ago, the couple set out to visit Bonnie’s hometown in Lusaka, Zambia, and ended up staying to be near her family.

By this time, the Jewish community was much smaller than it had been at its peak in the 1950s, when there were more than 1,000 members. By the 1980s, there was no longer a rabbi or a shochet, and kosher food had to be imported. When the third Abutbul child was born, a baby boy, Bonnie and Shlomo had to bring a mohel from South Africa for the brit milah and pay his airfare in and out of the country.

Jewish community members in Zambia, including Shlomo Abutbul, center, welcomed Rabbi Mendy Hertzel, left, to Lusaka on Purim.

The Rebbe’s First Emissary to Zambia

But while the Jewish population in Zambia was struggling, on the other side of the world, in New York, the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—was thinking about them.

Yerachmiel Glazer was born and raised in Zambia, in the town of Ndola. He remembers an elderly Sephardic Jew named Elkayam, who built a shul for the Jewish community, and the members who tried their best to keep Jewish practice despite their limited knowledge.

In 1967, Glazer was 18 years old and traveled to Israel to volunteer on a kibbutz. Finding himself in a religious kibbutz, he began his journey of learning about Jewish practice and began studying in a yeshivah for baalei teshuvah, returnees to the traditions of their ancestors, in Kfar Chabad. Two years later, he made his first trip to New York to meet the Rebbe.

“I went into a private audience with the Rebbe,” recalled Glazer. “The Rebbe read what I wrote in a note about my family in Zambia, and my studies in Kfar Chabad. Suddenly, the Rebbe raised his holy eyes and said to me: ‘I would like you to return to Zambia and involve yourself in spreading Judaism there.’ ”

Yerachmiel Glazer, a Zambian Jew who had extensive correspondence with the Rebbe about the Jewish community there, speaks with Hertzel at the Kinus Hashluchim.

In response to Glazer’s surprise, the Rebbe gave further instructions. The young man was to continue in yeshivah in Israel for a while longer but begin writing letters home to his community, with explanations about each upcoming holiday for the community to hang up on the synagogue bulletins.

Six months later, Glazer’s father asked him to return home to help the family business. The Rebbe responded enthusiastically.

“He will fulfill the request of his parents that he visit them for a few months, and surely this will be used for the spread of Judaism, its practice, and above all, regarding practical mitzvot.”

During his stay in Zambia, Glazer was sure to travel around Ndola and the “copper belt,” where he would find Jewish people, help them put on tefillin or give them Shabbat candles, and teach them about Jewish practice.

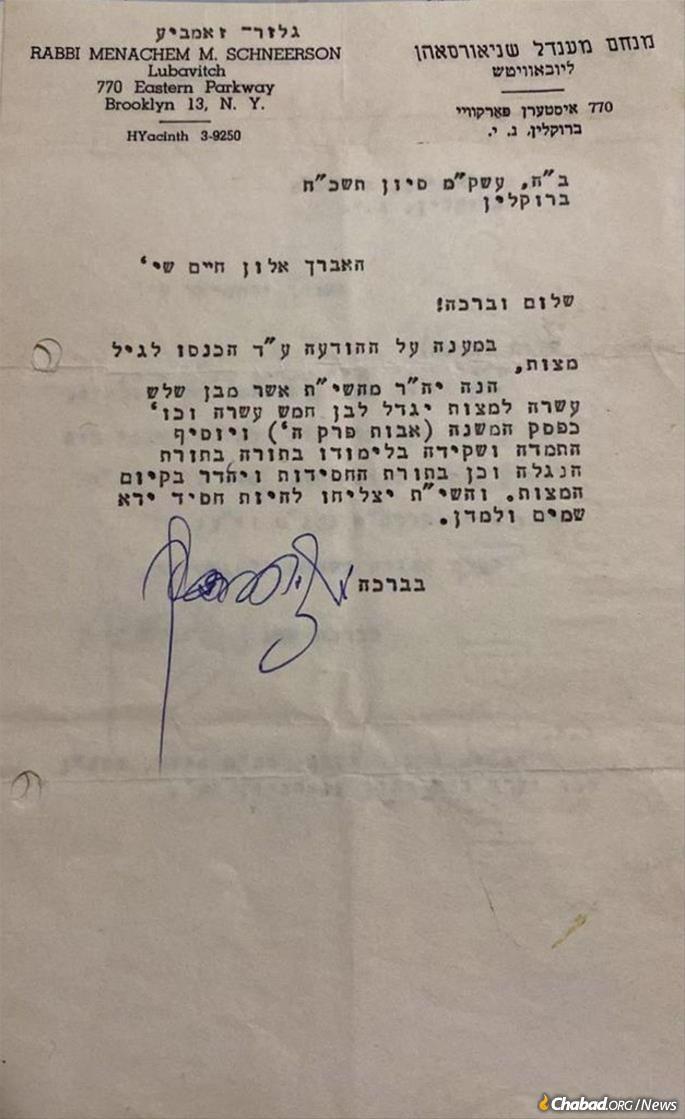

The Rebbe gave Glazer detailed instructions on how to inspire the Jewish community of Zambia during difficult times.

After nearly a year in Zambia, Purim was approaching—a holiday that was rarely celebrated by the Jewish community in Zambia. Glazer arranged for a Megillah to be sent to him from Israel and organized the first large Purim party in memory for the Jews of Zambia.

During his entire stay in Zambia, the Rebbe continued to send Glazer letters of support and instructions, showing the young man a level of respect reserved for men who were community leaders.

Soon, the political situation in Zambia became difficult for the Jewish community. After asking the Rebbe’s advice, Glazer moved with his parents and family to South Africa. As the Jewish community dwindled, the Rebbe continued sending emissaries on short missions through Africa, keeping in contact with the remaining Jews of Zambia.

Letter from blessing from the Rebbe to bar mitzvah boys in Zambia.

Today a resident of the Crown Heights neighborhood where he first met with the Rebbe in 1975, Glazer sat with Hertzel during the Kinus Hashluchim, where Glazer and the young rabbi discussed his youth in Zambia and how the Rebbe’s vision of a thriving Jewish community there is finally being fulfilled after more than 50 years.

Letter from the Rebbe to Yerachmiel Glazer.

The Royal Prince

A key member of that thriving community is Yehuda Bendavid, who was born into royalty. The Bemba tribe makes up about 36% of the Zambia population, and royalty is matrilineal. Bendavid’s mother’s royal title is Her Royal Highness Mumbi Mumbi of the Bemba Royal Establishment in the Northern Province of Zambia. Bendavid grew up as an African prince.

The Bemba tribe had been converted by Catholic missionaries in the late 15th century and throughout his early education, the young prince had many questions. Primarily, he didn’t understand why his teachers seemed to contradict themselves. On the one hand, he says, they said that G‑d never changed His mind, but on the other, they taught that G‑d had first chosen the Jewish people and then rejected them.

Rabbi Shlomo Bentolila, Mr. Yehuda Bendavid and Rabbi Mendy Hertzel at the banquet

“They didn’t let us ask questions,” says Bendavid. “So I had to keep wondering.”

Later, in law school, a peculiar encounter led him on a new journey. After joining a new class, a woman sat next to Bendavid and began talking to him.

“I know a time will come that you’ll play an important role in serving Israel and the Jewish people,” she said.

Bendavid responded with surprise, but she continued. “You are going to be a member of parliament and then president of Zambia. Your influence will spread across Zambia. You need to create an agenda for the African people to connect with Israel in order to advance. Israel is a light in the darkness.”

Initially, Bendavid thought the woman was spying on the royal family. But as he began to research her argument, he found truth to her words.

Her predictions began to come true. In 2006, Bendavid became a member of the Zambian parliament. In his capacity, he spoke about the importance of reconnecting with Israel.

At one time, Zambia had a good relationship with Israel. The Jewish community had been strong freedom fighters in the years leading up to Zambian independence in 1964 and established many successful economic centers, including a large university, hospital and farm block. Until 1973, the Zambian kwacha was a strong currency, on par with the GBP.

“All this was until the Yom Kippur war,” explained Bendavid. “Then the president of Zambia made a big mistake and withdrew our embassy from Israel, and confiscated many Jewish properties. At that point, the economy began to collapse. In 1991, a new president renewed relationships, and we began to recover.”

As a member of parliament, Bendavid campaigned against antisemitism and BDS measures. As he began to take trips to Israel, he felt a growing connection to the Jewish people. His searches online led him to Chabad.org, where he read everything he could about the Torah and Jewish people.

“I wanted to identify as Jewish, but I soon learned that it’s not like a religion you can just convert to. It’s a heritage and people. I felt that I had to leave parliament, and study in yeshivah full time.”

Bendavid at one of his fish farms in Zambia

In 2009, Bendavid left his parliamentary position and studied in a yeshivah in the Old City of Jerusalem. He eventually converted under the auspices of the Chief Rabbis of Israel. He returned to Zambia nearly a decade later as an Orthodox Jew and businessman, now concerned about the welfare of the Jews in Zambia, as well as the entire nation.

“The Rebbe had a vision of reaching every single Jew, and also teaching the children of Noach,” says Bendavid. “It is the duty of all Jewish people to be a light, and I believe that Zambia, a peaceful nation, is an excellent center for this light.”

Bendavid made contact with Rabbi Shlomo Bentolila, director of Chabad of Central Africa in Kinshasa, the Congo, and supported the rabbi’s efforts to establish a Chabad center in Zambia.

“The Jewish community in Zambia is very scattered,” Bendavid explained. “Divisions are normal; they are part of any heritage. But in Chabad, all Jews—Ashkenazi or Sephardi, religious or not—all are welcomed. A Jew is a Jew. Everyone feels they can attend Chabad.”

“I was amazed at how much Rivky and Mendel accomplished on their first visit here. They were able to identify more Jews than we knew of.”

Bendavid flew to New York to join Hertzel and 6,500 other rabbis and guests at this year’s convention.

“It is amazing to see the vision of the Rebbe being lived,” said Bendavid from New York. “The continuity of his vision is so very important. We need more connectivity among the supporters of Chabad so that we can continue to support this enormous undertaking of Chabad emissaries.”

Bendavid on his way to the Kinus Hashluchim

New Community President Looking Forward

Another key community member eager to welcome the Hertzels is Saul Radunsky, who has deep roots in the country and was instrumental in bringing Chabad there.

Radunsky’s father, Rachmiel, fled Europe as a young man in the 1920s, arriving in Livingston, Zambia, between 1929 and 1931 through South Africa. At the time, Zambia was under British occupation, and the copper business became very lucrative in the following decade since the British needed supplies to support the military efforts during World War II. Rachmiel Radunsky quickly found success.

But having fled persecution and prejudice in Europe, the young Radunsky quickly grew uncomfortable with the British treatment of the natives and joined the movement for independence.

“[Colonialism] was antithetical to my father’s values,” noted Saul Radunksy. “He was a strong activist for independence and was posthumously awarded the Order of the Grand Companion of Freedom by the government of Zambia.”

More important than business and political activism was Radunsky’s parents’ dedication to the Jewish community. At the time, there were about 120 Jews in Livingston, Zambia, including a rabbi and shochet. The rabbi taught in a cheder, which Saul attended. Saul’s father was the chairman of the Jewish community and his mother a WIZO activist. They put together money for the needy, kept a kosher home and welcomed dignitaries from Israel, including former Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and President Chaim Weizmann.

When Radunsky graduated from the small cheder at 11 years old, his parents sent him to a Jewish school in Cape Town, South Africa—a three-day train ride away.

“It wasn’t even the exhaustive traveling that showed how important Jewish education was to my father,” he said. “It was during the grips of apartheid in South Africa. My father was sheltering blacks who were caught in the conflict. I felt ambivalent. I was traveling between two worlds, and I knew how much my father detested it. But my Jewish identity today is secure because it was clear that not only did I have a Jewish heritage, I was able to evolve with Jewish tradition.”

Today, Saul Radunsky lives in Lusaka, Zambia, and is involved in connecting the diverse Jewish community. For that, he is looking forward to the arrival of Chabad emissaries to Zambia.

“My first interaction with Chabad was when Rabbi Mendy and Rivky Hertzel visited here last Purim, and what we found was that the essence of inclusivity had been adopted by [the Rebbe]; they had a practice that held us together, and I found that enlightening. They brought with them chassidut and Jewish ethos from a position that was non-critical and non-exclusive, so people felt included by that ethos. Which is why we embraced them.”

Community leaders Saul and Lisa Radunsky with visiting Rabbi Yehoshua Shmotkin

Eleventh Nation with Chabad in Central Africa

In 1991, the Rebbe sent Rabbi Shlomo and Myriam Bentolila to then Zaire, today Congo, to establish Chabad-Lubavitch of Central Africa. Until Myriam Bentolila’s passing in 2021, the couple oversaw the opening of 10 centers in 10 countries: Uganda, Angola, Ethiopia, Ghana, Congo, Ivory Coast, Tanzania, Nigeria, Kenya and Rwanda. Zambia was on Rabbi Bentolila’s radar for a long time. He often sent young rabbinical students to visit the Jewish community of Zambia to organize services for the holidays.

“Every time Chabad came, they’ve been very helpful,” said Radunsky. “In fact, I can’t see another way that the Jews in this community will find their identity without this. I can’t see another way. Because these guys reach out. It’s inclusive, as the Chabadniks have shown, that a Jew is a Jew is a Jew—that was a completely new thing for us, and that’s beautiful. So we look forward to having them.”

In April 2021, while Bentolila was sitting shiva for his wife, he announced that he would open a Chabad center in Zambia in her memory. Myriam had been a dedicated emissary to her community and committed to Jewish education in Central Africa as a whole. It would be a fitting memorial.

Rabbi Mendy and Rivky Hertzel were young newlyweds when Mendy’s friends began sending him word of Rabbi Bentolila’s announcement. At first, they laughed.

Rabbi Shlomo Bentolila holds a farbrengen with Zambian Jews.

‘We Want to Be Part of Their Story’

When Mendy Hertzel was a teen, he told his friends that he would find the place that scared him most and go there to open a Chabad center. He was partially joking, but now that jest caught up with him. As he and Rivky learned more about the Jewish community of Zambia, they realized this was it; this was where they were needed.

Mendy grew up in a small, artsy town in Israel’s northern Galilee called Rosh Pina. He was familiar with living at a distance from a major center of traditional Jewish life, but not as much as his wife, Rivky.

Rivky Hertzel, nee Greenberg, grew up in Alaska, where her parents are Chabad emissaries. Like Zambia, there isn’t much kosher food available there, so her parents have to import it from Seattle. Also like Zambia, the Jewish community in Alaska is fairly spread out and has its own culture, though, as Saul Radunsky aptly pointed out, Rivky will not need to bring her parka along.

The Hertzels already took their first visit to Lusaka, where they met members of the Jewish community and organized several community events—all of which were met with enthusiasm and full crowds.

“We landed on Taanit Esther, the day before Purim, with two events scheduled,” said Rivky. “We had 36 hours to shop and set up for the first event. Thankfully, the community was extremely helpful and showed us around.”

The Hertzels’ first 36 hours came with a sharp learning curve: There is no Walmart in Lusaka. They had to go to multiple small shops to procure all the items on their list. But they had their first event up and running.

Rivkah and Rabbi Mendy Hertzel returned to give a matzah baking class before Passover. They will be moving to Zambia before Chanukah.

After their visit, the couple said they really knew this would be their community, and so did Rabbi Bentolila.

“They did a great job,” the senior emissary commented. “It’s not easy to go to a place with a small number of Jews and gather everyone. It helps that they’re fluent in both English and Hebrew, so they can pull the community from all sides. Importantly, they’re good with children, and she’s an excellent teacher.”

The Hertzels plan to move to Zambia before Chanukah and will immediately begin with leading Shabbat services, holiday events, adult education and children’s programs.

Shlomo Abutbul said the community is eagerly awaiting their return and coming together in new ways: “Even before they arrived, new people showed up for Rosh Hashanah, which hasn’t happened in a long time. It’s very good.”

“The Chabadniks don’t understand how strongly the community appreciates their approach,” said Radunksy. “Their interventions are fabulous. We see their devotion that’s extraordinary, and we want to be part of their story if we can.”

Jewish children in Zambia experinece take part in their first

matzah bake.

Jewish man puts on tefillin.

Zambian Jew puts up a mezuzah.

As everywhere, children in Zambia will be a focus of Chabad’s work. Rivkah Hertzel with local Jewish kids on Purim, more than 50 years after Yerachmiel Glazer had the country's only Megillah shipped in from Israel.